Positivism versus post-positivism in international relations

There are many different theories of international relations (IR). These theories help us as students, analysts or academics to evaluate or predict the behaviour of states and non-state actors. It is important to understand the theories if you are interested in IR as a field of study.

According to Sterling-Folker (2006: p.5) as cited by Griffiths (2007), "IR theory is a set of template or prepackaged analytical structures for the multiple ways in which an event or activity...might be categorized, explained or understood. These templates may be laid over the details of the event itself, allowing one to organize the details in such a way that the larger pattern is revealed and recognize within and through the event."

The theories are further divided into 2 philosophical movements; positivism and post-positivism. In this article, I will begin by explaining both movements based on the required readings for the unit IR202 Theories of International Relations. Then I will try to categorize the 4 selected theories (realism, liberalism, constructivism and English School Theory) into the 2 movements. Finally, I will make my concluding remarks.

Positivism versus post-positivism

Sorensen (1998) believes that this is the core metatheoretical debate in IR after the Cold War. It has taken me awhile to fully grasp the debate and to distinguish one from the other. There is a lot of literature by scholars about positivism and post-positivism in IR theory. Smith as cited by Sorensen states that; "the two cannot be combined together because they have mutually exclusive assumptions".

According to Griffiths (2007) we have to distinguish epistemology from methodology before we try to understand positivism and post-positivism. He said: "epistemology is the philosophy of knowledge or of how we come to know. Methodology is focused on the specific ways that we can use to try to understand our world. Epistemology and methodology are intimately related: the former involves the philosophy of how we come to know the world and the latter involves the practice."

Post-positivism as described by Burchill and Linklater (2005) rejects

the possibility of using scientific methods to explain state behaviour. In particular, Smith, Booth and Zalewski (1996) cited by Burchill and Linklater said post-positivism rejects the possibility of the science of IR which uses standards of proof associated with the physical sciences to develop equivalent levels of explanatory precision and predictive certainty.

In

light of the changes that took place in the field of economics,

scientific methods adopted from the field of

economics helped to understand and predict with some degree of accuracy

the behaviour of states and non state actors. Positivism offered an

alternative with the use of rational choice or cost and benefit

analysis.

Brown and Ainsley (2005, p. 40) states

that rational choice thinking presuppose that politics can be understood

in terms of goal-directed behaviour of individuals, who act rationally

in the minimal sense that they make ends-means calculations designed to

maximize the benefits they expect to accrue from a particular situation.

In other words, a decision is rational when the benefits outweigh the

cost.

A

statement that is made on page 58 of their book helps us to understand

the post-positivist movement. They said post-positivists reject the

epistemological stance of rational choice theory. More generally, they

said post-positivists reject the 'foundationalist' account of the world,

in which knowledge can be ground by the correspondence of theory to a

knowable reality.

Griffiths, O'Callaghan and Roach (2008, p. xii) describes positivism as a philosophical movement that emphasizes 3 factors:

- Science and scientific factors as the only source of knowledge.

- A sharp distinction between the realms of fact and value.

- A strong hostility towards religion and traditional philosophy.

Furthermore,

they state that positivists believe in only 2 sources of knowledge (as

opposed to opinion): legal reasoning and empirical experience. The

positivist world view is that science is seen as the way to get at

truth, to understand the world enough so we might predict and control

it.

Loughlin (2012) defines positivism as 'the adoption of methodologies of the natural sciences to explain the social world'.

His definition follows Hume's radical empiricist conception of cause:

knowledge does not exist outside of what we can observe, and thus what

we claim to know is simply the associations or 'conjunctions' made on

these observations.

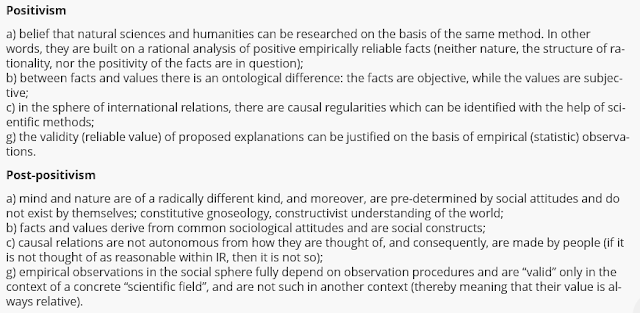

The table of main points shared by Katehon is another learning resource that we can use to help us differentiate positivism from post-positivism. Below is a screenshot of the table from their webpage titled 'A review of the basic theories of international relations':

Diagram 1 is a simplified typology outlining the difference between positivism and post-positivism. It looks simple but in reality the debate between both philosophical movements is complex. There is a wide range of literature about the debate and the emergence of new theories based on the philosophical movements.

|

| Diagram 1: A simplified typology |

Categorization of 4 selected theories

Realism and liberalism are listed under the positivism banner by Katehon. The argument is that both operate with empirically observable "positive" realities, confirming themselves through their appeal to them or by criticizing the theories of their opponent.

In reference to Diagram 1, I initially thought realism and liberalism were post-positivist. Griffiths, O'Callaghan and Roach (2008) listed critical theory, constructivism, feminism and postmodernism as notable theories under the post-positivist movement. Their emergence now show that positivism is no longer dominant in shaping the nature and limits of contemporary IR theory.

Another categorization by Katehon divides between radical and non-radical branches. Critical theory, postmodernism and feminism are categorized as radical in comparison to historical sociology and normativism. Constructivism is said to be in between because it shares some similarities with both positivism and post-positivism.

Sorensen (1998, p. 87) groups realism, liberalism and some versions of Marxism under positivism. He also groups critical theory, historical sociology, normative theory, and several versions of postmodernism and feminist theory under post-positivism. However, he argues that most of these positions associated with either one can be placed in the productive middle ground between the positivist and the post-positivist extremes.

Smith as cited by Sorensen (p. 90) grouped variants of realism, liberalism and Marxism under the label of post-positivism/reflectivism. I did likewise when I interpreted Diagram 1. Sorensen and other scholars believe in a middle ground between positivism and post-positivism, that is why the debate is ongoing.

I would classify the English School theory as a post-positivist theory. Some will argue that it is positivist. You can figure out by yourself where you would like to categorize by reading the many arguments put forward by various IR scholars.

Conclusion

The debate about positivism and post-positivism is complex and ongoing. Positivism is a philosophical movement that talks about the use of scientific methods, while post-positivism talks about the use of non-scientific methods.

In this brief article, I tried to pick out the main arguments and statements made about both philosophical movements and juxtapose with the each other in order to help you develop a basic understanding. If you are interested, you can continue to read more in order to develop your understanding about the 2 philosophical movements.

References

New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Burchill, S. & Linklater, A. (2005).

Introduction. In S. Burchill et al, Theories of international

relations (3rd ed.) (pp. 1-28). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Griffiths, M. (2007). Worldviews and IR theory: conquest or coexistence. In M. Griffiths

(Ed.), International

relations theory for the twenty-first century (pp. 11-20). New

York: Routledge.

Griffiths, M., O’Callaghan, T., & Roach,

S. C. (2008). International

relations the key concepts (2nd ed.). (pp.

268-270). New York: Routledge.

Comments

Post a Comment